They, too, had a dream.

In 1979, after Congress had yet again failed to make Martin Luther King Jr. Day a national holiday, a group of students from an Oakland high school refused to take “no” for an answer. To the contrary, the Apollos—members of Oakland Technical High School’s Class of 1981—became students on a mission.

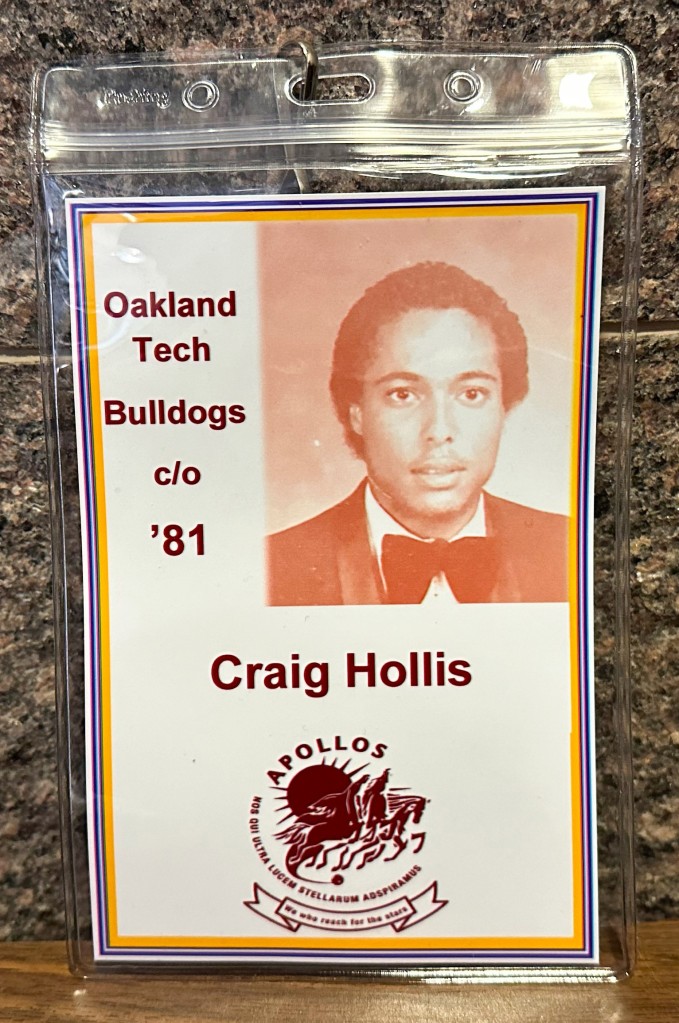

Count longtime CalVet employee Craig Hollis among them; and while they couldn’t go to Washington, D.C., they instead went 80 miles east to make their point.

Over the next two years, Hollis and his classmates made repeated trips to the State Capitol to attend legislative sessions and engage with lawmakers. Other students canvassed the neighborhoods in Oakland to generate awareness and support for the holiday.

“They were surprised to see us high school kids going around explaining the Martin Luther King holiday,” said Hollis, an office technician at CalVet headquarters in Sacramento since 2010. “They encouraged us.”

These Apollos—each class at the high school adopted on its own unique name—already represented a groundbreaking bunch. They were the first class to enter as freshmen since the 1930s. Until then, middle school went through 9th grade and students entered Oakland Tech as sophomores.

During a U.S. History class in 1979, instructor Tay McArthur told his students that Congress had once again failed to make MLK Day a national holiday. No national holiday honored an African American or person of any other minority group. Illinois became the first to create it as a state holiday in 1973.

His students began developing their plan of activism and turned their focus on Sacramento. It took them roughly two years to rally the support that included legislators from conservative Orange County before they finally prevailed.

On September 3, 1981, Governor Jerry Brown signed the holiday into law.

“When we were told it passed, we were like, ‘Get outta here!’” Hollis said. “Like, wow! We did it! They celebrated around the school. But it didn’t really kick in until we got to celebrate the holiday we’d created, when people have their day of service.”

Which they and other Californians did just over four months later when, on January 15, 1982, the state celebrated MLK Day officially for the first time. Congress, meanwhile, voted a year later to make it a national holiday, observed beginning in 1986 as a three-day weekend under the Uniform Monday Holiday Act (1968).

The school in 2020 produced a play depicting the Apollos’ work and honoring their achievement.

Hollis continued his pioneering ways when he became the first African American member of the Capay Volunteer Fire Department in the Yolo County community of Guinda. Last year, he celebrated his 20th year with the department, and is now a captain.

And in 2021, the Apollos celebrated the 40th anniversary of their history-making achievement with an event at Oakland’s Jack London Square. Their teacher, McArthur, was unable to attend.

“McArthur was in a care home, in hospice,” Hollis said. “We did a video to show him at the home. We all got to say ‘hello,’ and to thank him for motivating and pushing us. We all got in there and pulled together to make it work. We still get together, hang out, and talk about what we did to get together as a unit to get it accomplished.”

Indeed, there is no greater civics lesson than successful activism based on a dream, and one that comes true.

For more about Martin Luther King Jr., read this 2020 CalVet Connect story about his legacy https://calvetconnect.blog/2020/01/17/kings-impacts-on-the-civil-rights-movement-still-alive-nearly-52-years-after-his-death/.

Beautiful article CalVet.

Thank you Craig!

LikeLike

Craig, that is awesome!

LikeLike