On the evening of June 25, 1996, Latia Suttle settled in for the night in her quarters in the United States Army’s housing at the Khobar Towers complex in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. At least she thought she had.

“We were there on a peacekeeping mission,” Suttle said.

The marble floor suddenly sank beneath her feet. The pane in the sliding glass door bowed in her direction.

“I knew immediately it was a bomb. People started running into the suite saying to get out.” Suttle said.

She did not immediately know which of the dozens of buildings in the Khobar Towers housing complex had been attacked, though she would soon find out. Terrorists had loaded a truck with 5,000 pounds of explosives and detonated it in front of a building not far from hers. They killed 19 U.S. airmen and wounded more than 350 others. The assailants escaped.

Black History Month, as so many people astutely note, tells the history of America. While it often focuses upon the historical victories and struggles of Black Americans in this nation, it can also showcase patriots like Suttle, a Southern California veteran whose story remains a work in progress.

Suttle planned to join the Army reserve right out of high school in Fort Wayne, Indiana, in 1993. Hoping to use GI Bill benefits for college later, she converted to active duty in 1994, beginning a career that went on to span two decades.

Suttle worked in the Air Defense Artillery unit’s motor pool. Her first deployment took her to Dhahran, where she managed the civilian vehicle fleet, working with private contractors who were under the direction of the Saudis.

The Khobar Towers complex was home to roughly 2,000 American military personnel assigned to patrol the no-fly zone established over southern Iraq after the Persian Gulf War ended in 1991.

The explosion blew off the front of Building 131, which housed Air Force personnel. Among the 19 killed were three Californians: Captain Leland Haun of Clovis; Airman First Class Joshua Woody of Corning; and Airman First Class Justin Wood of Modesto.

Minutes after the blast, and still unclear of the devastation, Suttle and other soldiers responded.

“They needed somebody to dig through the rubble,” she said. “It was total chaos. It was so dark we couldn’t see if somebody was still there and was going to attack us.”

As she neared Building 131, she saw chunks of concrete on the ground. Then she saw the front of the building – gone.

“I looked up and it took my breath away,” Suttle said. “It started hitting me when I looked up (into the building’s exposed rooms) and saw there were no people.”

She dug through rubble. She helped survivors with first aid and by comforting others. Some worried they would might never see their families again, she said. Even after seeing the devastation first-hand, the scope of it still shocked her when she saw a news report on CNN that night.

The next day, she spoke to her mother back in Fort Wayne. Mom, too, had seen the report on CNN.

About two weeks later, Suttle’s unit rotated back to Germany. Subsequent deployments took her to Belize, South Korea, Kuwait, and Iraq.

Having built an impressive resume, she set about her goal of becoming a warrant officer. “I had lots of training under my belt,” she said. “But there was not a lot of information for people to become warrant officers.” Suttle said some of the advice she did get was disingenuous and intended to derail her pursuit, not enhance it.

“They wouldn’t give me correct information,” she said. “A white officer saw all that I had done and was totally shocked. I guess he thought I was dumb. ‘You did all of this?’ It was more old white men you see in those positions and not young African American women.”

When she became a warrant officer, she made sure others did not endure the frustrations she experienced. “I made sure people had the right information,” Suttle said. “I paid it forward.”

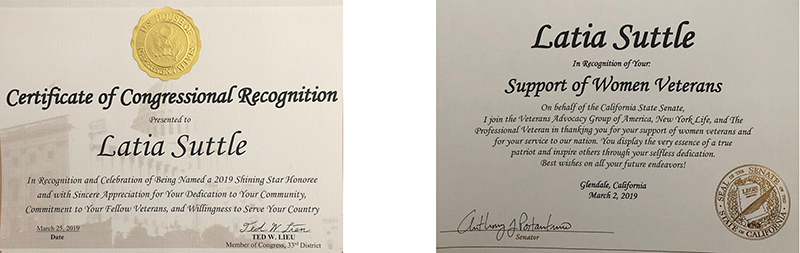

She continues to do so as a civilian. Suttle retired in 2014 as a Chief Warrant Officer II and lives in Southern California. A divorced single mom, Suttle began volunteering to advocate for veterans involved in divorce and custody cases. Suttle said she developed PTSD while she was still in the Army. She helps other veterans navigate a family and children’s court system that does not recognize a veteran’s military service, but will consider a veteran’s PTSD in its judgments.

“There are veteran criminal courts and substance abuse courts,” she said. “They ID vets in other courts but not in (family court).

She is also active in the NAACP, the American Legion, and the National Association of Black Military Woman.

Suttle served her nation with honor. Now she uses her experience to help others who have done the same.

It is her story, and a work in progress.

So proud of Ms. Suttle.She does an awesome job as our National Public Relations Chair. She is very motivated, enthusiastic and motivated. NABMW is fortunate to have her as a member of or team.

Patricia Jackson-Kelley

National President, NABMW

LikeLiked by 1 person