It took some time, but Chuck Woodson learned what many veterans and others dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) eventually come to accept: that the first step in dealing with the disorder is being able to talk about it.

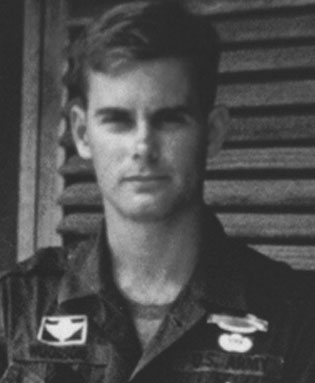

The 75-year-old Aptos resident and Army veteran left the military after fighting in Vietnam in the 1960s. He re-enlisted in the Army in1985, serving until his retirement in 2006. The second stint brought back the emotions and ghosts from the first, he said, and he wasn’t ready to deal with it when he returned to civilian life.

June 27th is PTSD Awareness Day. PTSD often is the result of experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event, and combat veterans represent a higher-risk group. Its intensity or severity can vary from person to person.

According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for PTSD, about 11-20 out of every 100 Veterans (or between 11-20%) who served in Operation Iraqi Freedom or Operation Enduring Freedom have PTSD in a given year. About 12 out of every 100 Gulf War Veterans (or 12%) have PTSD in a given year. And About 15 out of every 100 Vietnam Veterans (or 15%) were currently diagnosed with PTSD at the time of the most recent study in the late 1980s, the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (NVVRS). It is estimated that about 30 out of every 100 (or 30%) of Vietnam Veterans have had PTSD in their lifetime.

PTSD Awareness Day is important, Woodson said, because those with PTSD need to know help is available, and others need to understand what those with the disorder are experiencing.

“In the Army, you don’t talk about your weaknesses and vulnerabilities,” Woodson said. “You can’t come out of the military and be the same person you were when you went in. We need help, but there’s a lot of denial, putting stuff away. You suck it up and go about your business. And when you get out of the military, you don’t seek help.”

Woodson said it is now his goal and passion to encourage others to get the kind of treatment he has received over the past 13 years. Through counseling at the Santa Cruz Vet Center, he has been able to address the anger and agitation that once consumed him – “battle rhythm” he calls it – which could have ended his marriage and made friendships and other relationships difficult, if not impossible.

At the urging of another veteran and friend, and his wife, Woodson sought treatment. Vet Centers are the first places many veterans go to begin treatment. They are funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. There is an eligibility criteria, but veterans don’t need to be in the VA healthcare system to receive their services. Those include individual and group counseling, family counseling for military-related issues, and military sexual trauma counseling and referral, among others. They can also receive treatment at VA Health Care Centers.

Woodson’s first individual counseling session opened his eyes to his PTSD because the counselor – in a matter of minutes – tapped into so much of what he was feeling.

“She said, ‘You have this vigilance,’” Woodson said. “‘Are you comfortable sitting in a restaurant with your back to the door? When you’re on the beach in Santa Cruz or Monterey, you feel like the enemy is ready to assault the beach?’ I did have that feeling, that there was an enemy sneaking up from behind, still thinking that I was in harm’s way. In battle, you’re always thinking worst-case scenario.”

After getting him to understand the depth of his PTSD, the counselor recommended that he participate in group sessions.

“No, no, no, no, no!” he said. “I don’t see that happening. I don’t see me sitting there with other guys. Shield’s up. I don’t want to be talking about it with other guys.” Eventually, Woodson did attend group sessions, overcame his initial discomfort, and opened up.

“It created the bond,” he said. “We have the same issues. We’re warriors. We have the same problems. By being in a group dynamic, we help each other.” Even so, it took time to understand the process.

“I asked some of the guys, ‘How long do we attend these,’” Woodson said. “They started laughing. I thought you went to the class, passed a test, got a certificate, and that was all there was to it.”

A friend named Phil dispelled that notion. “He said, ‘With PTSD, you may never get over it. It may stay with you the rest of your life.’ He was right. I’m still in therapy today.”

And happy to talk about it.

About PTSD Awareness Day

PTSD Awareness Day first was recognized in 2010. Orchestrated by a U.S. Senator from North Dakota after a National Guardsman from his state committed suicide following two tours of duty in Iraq.

But PTSD is by no means a relatively new disorder. The National Center for PTSD cites a series of studies from after the Civil War through 2013, and under numerous other names including “nostalgia,” “soldier’s heart,” “shell shock,” “battle fatigue,” and others.

The American Psychiatric Association referred to the disorder as “gross stress reaction” in its first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, dubbed DSM-1, in 1952. By 1980, the association included PTSD in DSM-3, based upon studies involving Vietnam War veterans, Holocaust survivors, victims of sexual trauma, and others, while linking war trauma to civilian life among veterans who were in the military.

In 2013, DSM-5 concluded that PTSD is a common disorder that will be experienced by 4 percent of all American men and 10 percent of American women in their lifetime, and that PTSD is now categorized among Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders. A person must have all four basic symptoms – reliving the traumatic event, avoiding situations that remind them of the traumatic event, having negative changes in beliefs and feelings, and over-reacting to situations – to be diagnosed with PTSD.

Know the Signs of PTSD and Seek Help

Reliving the event — Unwelcome memories about the trauma can come up at any time. They can feel very real and scary, as if the event is happening again. This is called a flashback. You may also have nightmares. Memories of the trauma can happen because of a trigger — something that reminds you of the event. For example, seeing a news report about a disaster may trigger someone who lived through a hurricane. Or hearing a car backfire might bring back memories of gunfire for a combat Veteran.

Avoiding things that remind you of the event — You may try to avoid certain people or situations that remind you of the event. For example, someone who was assaulted on the bus might avoid taking public transportation. Or a combat Veteran may avoid crowded places like shopping malls because it feels dangerous to be around so many people. You may also try to stay busy all the time so you don’t have to talk or think about the event

Having more negative thoughts and feelings than before — You may feel more negative than you did before the trauma. You might be sad or numb — and lose interest in things you used to enjoy, like spending time with friends. You may feel that the world is dangerous and you can’t trust anyone. It may be hard for you to feel or express happiness, or other positive emotions. You might also feel guilt or shame about the traumatic event itself. For example, you may wish you had done more to keep it from happening.

Feeling on edge — It’s common to feel jittery or “keyed up” — like it’s hard to relax. This is called hyperarousal. You might have trouble sleeping or concentrating, or feel like you’re always on the lookout for danger. You may suddenly get angry and irritable — and if someone surprises you, you might startle easily. You may also act in unhealthy ways, like smoking, abusing drugs and alcohol, or driving aggressively

Seeking Help

To get help for PTSD, call 1-800-273-8255. Press “1” if you are a veteran.

Call 911 or visit a local emergency room

Visit a VA Health Care facility or Vet Center in California.

Another great article! My dad had a bad case of it, but back then it wasn’t identified as such. So thankful we are opening our eyes to what our service families go through. Lesa CanenTurlock, CA

LikeLike